Fact: The rates with which ADHD is diagnosed vary so much primarily due to diagnostic criteria and measurement methods used.

When people say that “ADHD is overdiagnosed” they are usually referring to the routine practice in a particular region or country.

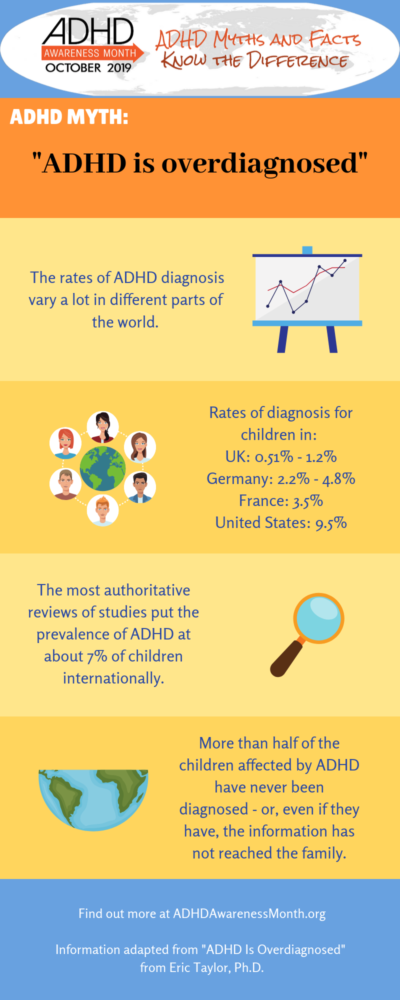

The rates with which ADHD is diagnosed do indeed vary so much in different places that it is natural to consider the possibilities both of over- and under- diagnosis. Both can apply in different countries and at different times. In Europe, the rates for diagnosis have mostly been rising, often from a very low level in the 1980s.

- In the UK, when families are asked if their child has ever received a diagnosis from any source, the rates for children of school age are around 1.2%. However, from the analysis of a primary care database the rate is only 0.51%.

- In Germany, the equivalent rate has been estimated at 2.2% for full diagnosis and 4.8% for “ADHD features.”

- In France, a representative population survey found that 3.5% of children had been treated for inattention and/or hyperactivity.

In the USA, by contrast, rates are rather higher and vary from state to state. In 2007, a national survey of parents found that 9.5% of children aged 4 to 17 had received a diagnosis.

How do these rates compare with the actual rates of ADHD in the populations?

Does this mean that ADHD is overdiagnosed in the USA and underdiagnosed in Europe? Not necessarily.

To answer that, we must ask how these rates compare with the actual rates of ADHD in the populations. The true rates are not so easy to define. Inattention and hyperactivity-impulsiveness are distributed as dimensions in the community. There is no unchallengeable neurobiological cut off to establish what levels should or should not be regarded as a disorder.

Accordingly, the research diagnosis of ADHD is based on international consensus and longitudinal research. Many studies in many countries have agreed that this research diagnosis represents a valid medical syndrome, with characteristic predictions to neurobiology, psychological function, course and treatment outcome. Epidemiological research has found prevalence does not vary much between countries.

The most authoritative reviews of studies put its prevalence at about 7% of children internationally. The differences are based mainly on the exact diagnostic criteria and measurement methods adopted. These figures for rates of research disorder can be seen in more detail in a recent review . In short, in Europe there are much higher figures for the actual rates of ADHD (the research prevalence) than for the rates with which ADHD is recognised (the administrative prevalence).

The conservative implication is that more than half of the affected children at any one time have never been identified as such – or, even if they have been, the information has not reached the family. This obviously does not imply over-diagnosis.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Eric Taylor FRCP FRCPsych(Hon) FMedSci is Emeritus Professor of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry at King’s College London Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience. He has received the Ruane Prize from NARSAD, the Heinrich Hoffman medal from the World ADHD Federation, an ADDISS Award, and the inaugural President’s Medal from ACAMH.

References

Taylor, E. (2017). Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: overdiagnosed or diagnoses missed?. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 102(4), 376-379.