Fact: ADHD is really a problem with the chemical dynamics of the brain and it’s not under voluntary control.

It’s easy to see why many people believe that ADHD is just an excuse for laziness. Everybody who has this disorder has a few activities or tasks where they have no significant difficulty in exercising those same functions that are usually quite difficult for them: paying attention, prioritizing tasks, getting started, sustaining effort, managing emotions, and keeping several things in mind at once.

They may focus very well on playing a sport they enjoy or on playing video games or making art or playing music or repairing a car engine. Yet they are unable to demonstrate that same kind of focus and self-management for their schoolwork or their job.

Noticing that contrast from one situation to the other can certainly lead someone to ask, “If you can do it for this, why can’t you do it for these other tasks that you know are important? Aren’t you just being lazy?”

The fact is that ADHD often looks like a lack of willpower, an excuse for laziness, when it’s not!

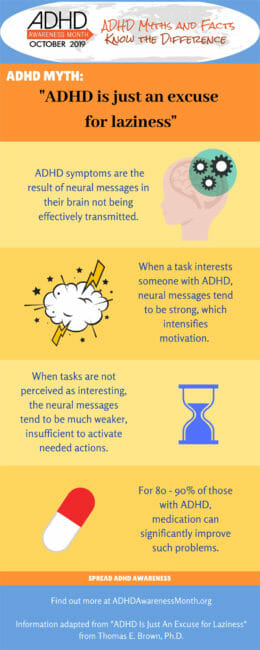

ADHD is really a problem with the chemical dynamics of the brain. It’s not under voluntary control. People with ADHD can be lazy from time to time like anyone else, but that is not the explanation for their symptoms. Their ADHD symptoms are the result of neural messages in their brain not being effectively transmitted, unless the activity or task is something really interesting to them, something that, for whatever reasons, “turns them on.”

One of my patients once said:

“I have a sexual example for you that shows what it’s like to have ADHD. It’s like having ‘erectile dysfunction of the mind.’ If the task you’re trying to do is really interesting to you, you’re ‘up’ for it and you can perform. But if it doesn’t turn you on, you can’t ‘get it up.’ And it doesn’t matter how much you say to yourself, ‘I want to, I need to, I should,’ you can’t make it happen because it’s just not a willpower thing!”

In fact, for people with ADHD, neural messages related to tasks that strongly interest them tend to be strong, bringing intensified motivation.

For tasks they do not perceive, either consciously or unconsciously, to be quite as interesting the neural messages tend to be weaker. If messages are not sufficient enough to activate a person, it is likely to make a them seem unmotivated or lazy.

For 80% or 90% of people with ADHD, medication can significantly improve such problems.

About the Author

Thomas E. Brown, Ph.D. is Director of the Brown Clinic for ADHD and Related Disorders in Manhattan Beach, CA. and Adjunct Clinical Associate Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at the Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California. His web site is www.BrownADHDClinic.com

Resources

- Volkow, N.D, Wang, GJ, Newcorn, JH, et al: Motivation deficit in ADHD is associated with dysfunction of the dopamine reward pathway. Mol Psychiatry 16 (11) 1147-154. 2011

- Volkow, ND, Wang GJ, Tomasi, D, et al: Methylphenidate-elicited dopamine increases in ventral striatum are associated with long-term symptom improvements in adults with ADHD. J. Neurosicence 32 (3): 841-849. 2012